Hunters begin the "Frog Season" by making the first "gig" at the stroke of the midnight hour, right at the start of the DNR frog gigging window. The "giggers" start scouting ponds and lakes for frogs to hunt a couple hours before midnight, where they look at the frogs' sizes and their location in and around the ponds. The gig involves all participants collaborating in scouting the frogs and then taking turns hunting. A gig - a multi-pronged spear - is used to impale frogs at the edge of the ponds from the top, a process that requires practice and skills, given the agility of the frogs in and around water.

A gigger with a BullFrog (Lithobates catesbeianus) that he just hunted with his gig.

Giggers after a Gigging session at the Cold Friday pond in Harrison-Crawford State Forest.

Giggers use a variety of equipment and tools to hunt the frogs. These include high power lights, gigs, collection baskets, pistols and small boats. Boats are used to hunt larger frogs in the centre of the ponds. Usually in a pair, giggers paddle the boat and sometimes wade in the water alongside to reach the centre. The person sitting at the back pilots the boat while the person sitting in the front directs and makes the gig. Wading and boating for gigging displays a sense of spatial awareness and attachments to place, which, here, is the pond. Once hunted, a pond is left alone for a couple years to revive.

Research Talk presented at Purdue University, April 2022.

*recording courtesy Puneeth Boni*

Public Communication Poster from the research.

Presenting the poster at the Society for Applied Anthropology (SfAA) Annual Conference at Salt Lake City, March 2022.

O’bannon Woods State Forest, Corydon, IN

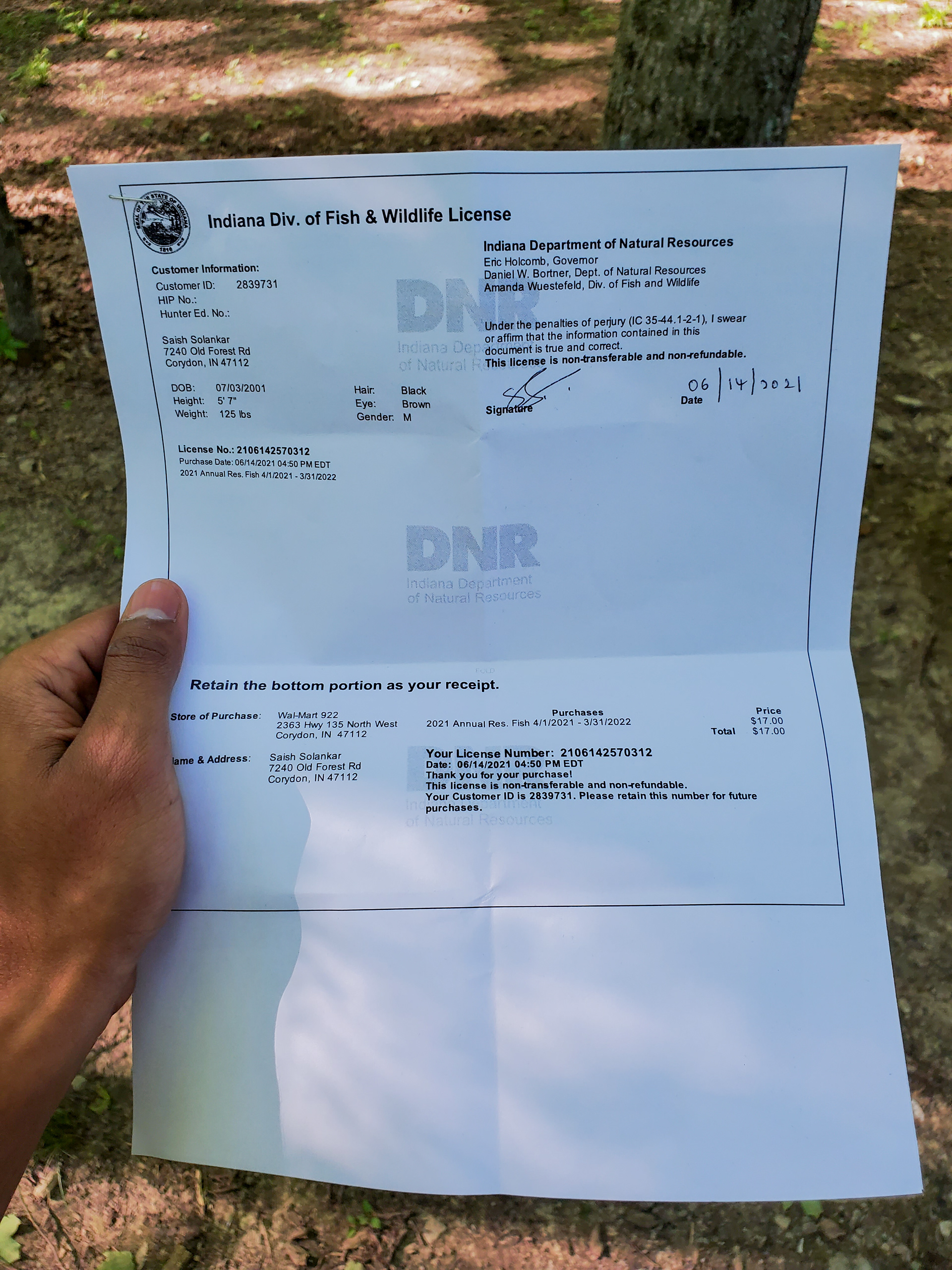

Walmart sporting section: Where you get your fishing licence (required for frog gigigng) from.

Gigs and the collection basket used to hunt and store the frogs.

A frog-gigging license.

Giggers scout the ponds for ideal frogs to hunt.

Hunters catching frogs bare handed before the start of the season to exercise their skills.

A bullfrog just hunted by a gig (a multi-pronged spear) during a hunt.

A bullfrog being transferred to a collection basket.

Frogs collected in the collection basket, which is an important tool for gigging.

Giggers pose with large frogs that they collected during the gig.

Wyatt leads a boat into the pond. He will wade along the boat for a while before hopping into it.

Wyatt locates a frog in water from his boat.

Hunters venture out into Cold Friday Pond to hunt the bigger frogs in the middle of the pond on a two person boat. The person sitting behind pilots the boat and the person forward directs and makes the hunt.

Giggers pose with large frogs that they collected during the gig.

Hunted frogs placed on a wooden board for counting, with a hunter’s knife that will be used for processing.

Giggers preparing for the processing and butchering of the meat, while the bodies of the dead frogs lie in the foreground.

Hunters begin processing the hunted frogs for the meat of their legs.